This post is longer than most, but I got some splainin to do.

I have been baking a lot of sourdough bread these last several months and there are more than a few posts featuring this. Some have actual recipes and others more descriptive. I was reading back what I have posted, there are terms and references unexplained. If you are a baker these things are a given. But if not this post may help explain things a bit. Others have given similar information, but sometimes a different perspective can be helpful.

Sourdough Starter

Most people use a commercial yeast for bread. It comes most frequently in the small packets at your local mega mart pre-measured for your convenience. You can buy active dry or instant. There is also fresh cake yeast but that is another topic altogether. Almost all commercial baker’s yeast is of the variety Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It has been been the dominant strain for commercial baker’s since the turn of the 20th century when advances in science made it possible to easily produce in large quantities. It produces a taste we have all come to expect in the bread we buy retail.

Sourdough bread however is produced with the yeast that is most commonly in the flour that we buy. Yeast is everywhere in our environment. It lives on the wheat that flour is made from. The process to produce Bleached flour kills most of it but Unbleached flour and especially Whole Wheat flour is practically crawling with the little beasts. If we mix flour and water, then let it naturally ferment over time, we end up with sourdough starter that has a large enough volume of yeast to leaven our bread. In addition to the yeast in the original flour, wild yeast from each kitchen finds it’s way in and contributes to the biome.

One of the most common yeast strains from wheat is Saccharomyces exiguous. A major difference in this yeast is it’s symbiotic relationship with Lactobacillus. Quoting Wikipedia here “Broadly speaking, the yeast produces gas (carbon dioxide) which leavens the dough, and the lactic acid bacteria produce lactic acid, which contributes flavor in the form of sourness. The lactic acid bacteria metabolize sugars that the yeast cannot, while the yeast metabolizes the byproducts of lactic acid fermentation.” I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Levain

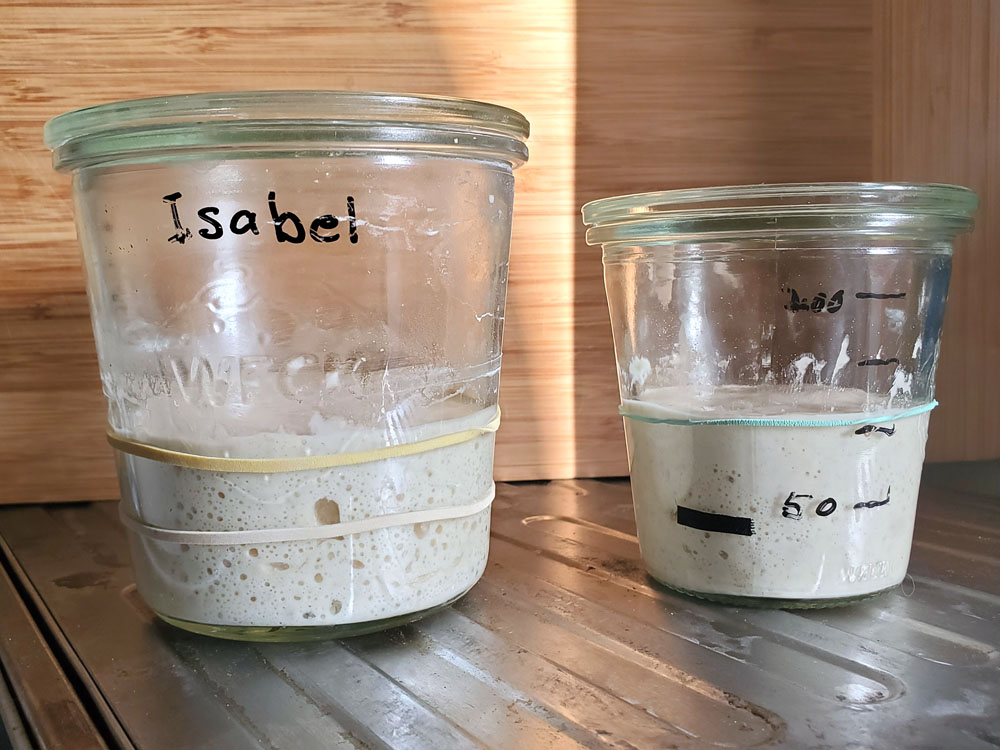

Generally, the starter, mine is called Isabel, is a yeast and bacteria pet if you will that you feed each day and watch grow then recede on top of the fridge. Some call it the mother and my Mother was Isabel. Levain on the other hand is an offshoot that is produced to make a loaf of bread today. I know from observational experience that between 7-9 hours after a feeding it is at it’s peak and ready to add to my autolysed dough.

Sometimes I will just take the needed amount from Isabel if I have not used another container to create a separate levain. As long as you have enough left over to maintain your mother this is fine but the safe thing is to use a separate batch just in case something bad happens such as contamination or dropping the whole batch on the floor. I even keep a small batch of starter in the fridge that I take out every 2 weeks and feed, just in case.

You can find much more complicated explanations but I’m trying to keep it simple. For most practical purposes, the terms starter and levain can be used interchangeably.

Autolyse

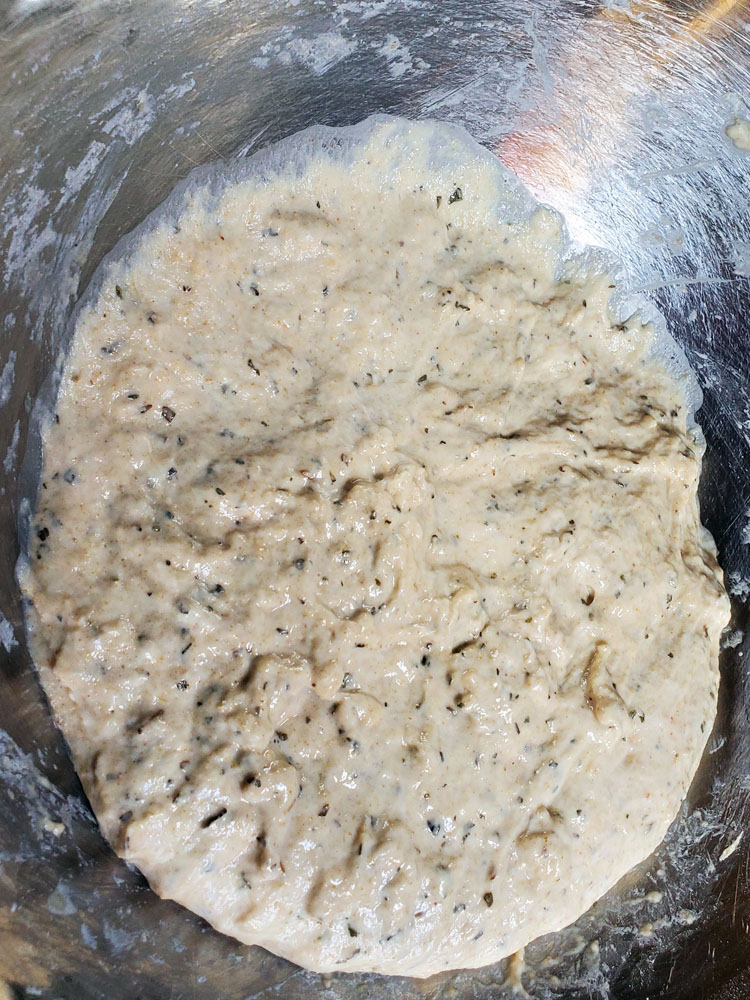

Pronounced auto leez, this is the first step in most of my sourdough bakes. Simply put, you mix flour and water then let the flour fully hydrate for 15 minutes up to several hours before adding the salt and starter. This step give a head start to the gluten development process and makes it easier for the dough to rise. After an hour of autolyse the dough is much smoother and easier to work with.

Baker’s Math

Most professional bakers use Baker’s Math to express ingredient ratios. Each ingredient is compared by weight to the weight of the flour used in the recipe. Flour is always 100%. For instance, a recipe that uses 250 grams of flour at 100%, 200 grams of water is 200/250 or 80%. You divide the ingredient weight by the flour weight to get a percentage. This allows a recipe to be easily scaled up or down. This can be almost impossible if using cups and spoon measures.

Hydration

This refers to how much water by percentage is contained in the recipe. The water in the starter needs to be accounted for as well as other water used.

My typical starter is 100% hydration which means it has as much water as flour. 50 grams of starter has 25 grams of water and 25 grams of flour.

The focaccia I bake most often has a hydration of 80%. For every 100 grams of water, I use 80 grams of water including the flour and water in my starter. Using Baker’s Math:

| Recipe Water | 195 gr | Recipe Flour | 250 gr | ||

| 50 gr Starter Water | 25 gr | 50 gr Starter Flour | 25 gr | Total Water/Flour | |

| Total Water | 220 gr | Total Flour | 275 gr | 220/275= .8 or 80% |

I recently made a modified focaccia with only 25 grams of starter or 10% inoculation. Using Bakers Math I adjusted the flour and water in the mix.

Inoculation

The percentage of starter or levain used in relation to the total amount of flour. The levain is used to inoculate or infuse the dough with yeast so it will rise. In my focaccia I usually use 50 grams of starter for 250 grams of flour or 20% inoculation.

Bulk Rise

2 quart Cambro

After the autolyse, the dough is inoculated with the levain or rising agent. It is then either kneaded or for my usual focaccia, a series of stretch and folds. After this it goes into a clean container for the Bulk Rise. It is called bulk because all the dough is together. Bulk rise can be at room temperature (RT) or in the cold (Retard) or a both. If making rolls or separating into different loaves is then left to rise again, hence 2nd rise.

2nd Rise

After Bulk Rise, the dough can be separated into loaves or rolls (shaping) and left to rise a 2nd time before baking. The time depends on the temperature and hydration.

Retard

Putting your rising dough into the refrigerator to slow the action of the yeast allowing a longer proofing time for added flavor. This also allows you to make your dough at night and bake in the morning.

Stretch and fold

This is a method of gently working the dough without kneading. It provides the levain with new food as it is exposed to new flour. Take your bowl of dough and with wet fingers, pull the dough from one side and lift and fold it over itself. Turn bowl ¼ turn and repeat 3 more times until you have worked the dough on all sides.

Boule

Ciabotta

Shaping

This one is easy. It refers to making the dough into the shape it will be baked. A boule is a round, batard is an oblong loaf, and a baguette is a longer skinnier loaf. The ciabatta were shaped into rolls. Focaccia is simply stretched to the shape of the baking pan.

Banneton

This a proofing basket that can be woven from either natural rattan or plastic. They cradle the shaped dough and help it keep it’s shape. They also allow the dough to breathe since they are not meant to be water tight. Often they are used with a cloth insert to prevent sticking. In the beginning, you can always use any oblong basket for a batard or bowl for the boule. I have used a French Fry basket for my batards and lined it with a piece of old cotton pillowcase.

Oven Spring

The amount of rise the bread has when put into a hot oven. If your bread rises tall in the oven you have a great Oven Spring. If you have a hockey puck then Oven Spring was poor.

Good Oven Spring and nice open Crumb

Crumb

The internal structure of the bread. Do you have large uneven holes or small close together holes? This is the crumb. When you take a bite, is it soft and airy or gummy? These are some of the words used to describe the crumb. If you have dropped small pieces onto the floor, that is a different crumb altogether.

A few other terms I have not used are Score and Lame since I rarely make loaves, I love focaccia. To score the bread is to cut or slash the top to prevent the dough from bursting elsewhere as it rises in the oven. The traditional tool to score is called a Lame, pronounced lahm. A traditional lame is a wooden, metal, or plastic handle that holds a double edged razor blade. When I need to score a loaf, I just use a single edged razor blade or sharp knife.

Sourdough Terms Explained: Is a Bread Lame really Lame?

Not that kind of Lame, what do you think I’m talking about?

Thus concludes my simplified explanation of common terms used for sourdough baking. This is not a complete list but the most common.

If even one term has become more clear, I have done my job.

Please help me grow by sharing on social media.